The Shingles Bell

Recommendation Bulletin for Shingles Vaccine to reduce Alzheimer's and Dementia Risk

Authors: Dr Robin Brown - R&D Physician, Dr Jack Kreindler - Founder, CEO

Overview

Shingles vaccination is a well-established way to reduce the risk and severity of shingles (Herpes zoster) and its often debilitating complications. In the last few years, multiple large population studies - now including “natural experiment” / quasi-randomised designs - have also reported a consistent association between shingles vaccination and a lower subsequent risk of dementia. Some of the strongest evidence suggests the effect may be greater in women.

These findings do not yet prove that shingles vaccines prevent Alzheimer’s disease (or dementia) directly, nor do they define the ideal timing for vaccination purely for neuroprotection. But the signal is now strong enough to justify a practical, evidence-aligned conclusion:

If you are already eligible for shingles vaccination, being up to date may have benefits beyond shingles prevention, and earlier than scheduled vaccination is rational to consider.

For people considering vaccination earlier than their national programmes routinely offer, the decision should be individualised, weighing baseline shingles risk, dementia risk factors, local guidance, and access.

A recommended starting point is for all those above 50 years of age to consider the Shingrix vaccine in conjunction with their physicians.

Background: Infection, Inflammation, and Alzheimer’s biology

Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias are multifactorial. Classic hallmarks include amyloid and tau pathology, but neuroinflammation and immune dysregulation are increasingly recognised as part of the disease process.

A compelling (but still actively debated) line of research proposes that chronic or recurrent infections - particularly herpes-family viruses - might contribute to neuroinflammatory pathways that influence amyloid biology and microglial function. Notably, amyloid-β has been proposed to have antimicrobial properties, supporting hypotheses in which infection-related immune activation could be one upstream driver of amyloid deposition in vulnerable brains. (See refs. 4–6.)

More broadly, several studies suggest that a richer vaccination history correlates with better later-life cognitive outcomes, potentially via reduced infection burden and/or immune modulation. The shingles-vaccine signal stands out because it has replicated across multiple datasets and study designs, including designs that substantially reduce confounding.

Shingles in brief: why vaccination matters for healthspan

Shingles occurs when varicella-zoster virus (VZV) - the virus that causes chickenpox - reactivates years later from latency in sensory ganglia. Risk rises with age and with immune compromise. Shingles can be intensely painful and prolonged, and may be complicated by post-herpetic neuralgia, ophthalmic involvement, and other serious sequelae.

Vaccination substantially reduces shingles incidence and complications - this remains the primary reason shingles vaccines exist. (Refs. 7–9.)

What the dementia data show

Natural-experiment / quasi-randomised evidence

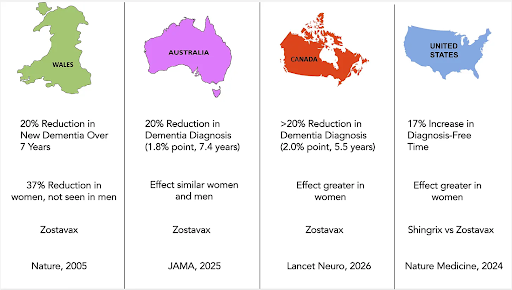

A major study in Wales exploited a date-of-birth eligibility cut-off in a national programme, creating a quasi-randomised comparison. Over ~7 years of follow-up, zoster vaccination reduced the probability of a new dementia diagnosis by 3.5 percentage points, corresponding to about a 20% relative reduction; the effect was stronger among women. (Ref. 1)

A similar approach in Australia—using the “just eligible vs just ineligible” threshold created by programme rules—also found a lower probability of dementia diagnosis over ~7.4 years among those eligible for vaccination. (Ref. 2)

More recently, a Canadian analysis using natural-experiment methods has added further supportive evidence in another health-system context. (Ref. 3)

These eligibility-threshold designs reduce many common biases in observational vaccine studies, because people on either side of an arbitrary cut-off are (on average) highly comparable. We can therefore have a high confidence that this result is not a statistical artefact or explainable by other variables such socioeconomic status or diet.

Fig. The above figure is taken from Dr Eric Topol’s in-depth explainer on these studies (see further reading below). The striking finding across all studies is that the protective effect of vaccination is primarily seen in females.

Vaccine-type comparisons: Shingrix vs older live vaccine

A large 2024 analysis reported that the recombinant, adjuvanted vaccine (Shingrix) was associated with lower dementia risk than the older live-attenuated vaccine (Zostavax), and the signal again appeared larger in women. (Ref. 10) This replicates the findings of the other natural experiment studies while also providing evidence that the newer Shingrix vaccine could provide better protection.

Systematic review and meta-analysis

A 2024 systematic review/meta-analysis concluded that herpes zoster vaccination is associated with reduced dementia risk, while emphasising the need for more high-quality studies and careful interpretation given heterogeneity and study design limitations. (Ref. 11)

Why might the benefit look larger in women?

The dementia-protective association appears more pronounced in women in the majority of these studies. (Refs. 1, 10). Women have a significantly increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s and this has usually been attributed to the fact that women live longer than men on average. However, that would not explain the difference we see in the shingles vaccine effect.

We currently have no clear explanation for this observed difference between the sexes. Possibilities include sex differences in immune response, baseline dementia biology, trajectories of immune senescence, different patterns of VZV reactivation and inflammatory response, and/or differential vaccine effects. This remains an under-researched and clinically important area.

What can we recommend now?

What we can say confidently:

Shingles vaccination is effective for shingles prevention and is generally safe. (Refs. 7–9, 12–14)

Multiple large studies link shingles vaccination with lower subsequent dementia risk, including designs that reduce the risk of confounding variables. (Refs. 1–3, 10–11)

What we cannot yet say:

We cannot yet claim shingles vaccination prevents Alzheimer’s disease specifically, nor define an “optimal” timing purely for neuroprotection.

We do not yet have randomised trials or prospective studies designed primarily to test dementia outcomes (though the quasi-experimental data makes the case for doing them).

Who should consider vaccination and when?

Every suitable adult approaching 50 should consider Shingrix vaccination: Timing variance depends on individual risk. The standard shingles programmes are as follows:

United States: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends 2 doses of Shingrix for immunocompetent adults ≥50, and for adults ≥19 who are or will be immunodeficient/immunosuppressed. (Ref. 12)

England (NHS): NHS offers shingles vaccination for those turning 65, those aged 70–79, and adults ≥18 with a severely weakened immune system (2-dose schedules; intervals vary by cohort). (Ref. 13)

UK practitioner guidance: national programme details - including phased cohort changes and dosing intervals - are summarised in UK government guidance. (Ref. 14)

Clinical takeaway:

If you are eligible anyway (by age or risk group), vaccination is already strongly justified for shingles prevention and the apparent protective effect for dementia association becomes an additional reason to be vaccinated.

For those considering vaccination earlier than their public programme offers, the conversation should be individualised: dementia risk profile (family history, vascular/metabolic risk, sleep, hearing, depression, etc.), immunological risk, shingles risk, and local access.

We strongly recommend all those over 50 years of age consider Shingrix with their physicians. Those younger to have a personalised risk adjusted consideration approach.

Which shingles vaccine?

The two main vaccines available are Zostavax and Shingrix. The majority of the epidemiological studies mentioned above involved vaccination with Zostavax which is a live weakened virus vaccination delivered in one dose under the skin. This vaccine has largely been superseded by Shingrix which contains a viral subunit and an adjuvant to stimulate the immune system.

Where available, Shingrix has largely replaced Zostavax due to stronger and more durable protection against shingles. In U.S. guidance, Zostavax is no longer used. (Ref. 12) As mentioned above, observational comparisons suggest Shingrix may also be associated with greater dementia risk reduction than Zostavax. (Ref. 10)

Safety and side effects

Most people experience short-lived local/systemic effects (sore arm, fatigue, myalgia, headache) for 1–3 days. Serious adverse events are rare.

A very rare increased risk of Guillain-Barré syndrome has been observed in post-marketing data; regulators required a warning, noting an observed association but insufficient evidence for definitive causality. (Ref. 15)

Overall, the safety profile of shingles vaccination is good and the benefits will outweigh the risks in most individuals.

Do you need boosters or antibody testing?

At present, booster doses are not routinely recommended in either U.S. or UK guidance for immunocompetent adults, largely because durability remains high and optimal boosting strategies have not been established. (Refs. 12, 14)

Clinical trial follow-up and long-term observational follow-up suggest shingles protection remains substantial for a decade or more after vaccination, supporting the current “no routine booster” approach. (Refs. 8–9, 16; see also refs. 17–18)

Antibody testing: Routine antibody testing to guide boosters is not a standard protocol, in part because antibody level alone may not capture protection (cell-mediated immunity matters), and protective thresholds are not clearly defined for individual decision-making.

Personalised testing after 10 years from vaccine remains a reasonable research question though not a standardisable recommendation.

Bottom line

Shingles vaccination is already a high-value health intervention for shingles prevention. The emerging dementia literature - now including quasi-randomised “natural experiment” studies - suggests it may also confer an additional neuroprotective benefit of around 16-20% relative risk reduction over 7 years followup, with signals that appear stronger in women.

A rational approach, until prospective trials clarify mechanism and optimal timing, is:

1. Consider Shingrix (GSK) vaccine, from Age 50, or earlier: As offered by your health service according to your local shingles vaccine programme (or earlier if you and your clinician judge the risk/benefit favourable), and

2. Regard shingles vaccination as one component of a comprehensive dementia / neuroinflammatory risk-reduction strategy - in combination with vascular/endovascular health, cardio-metabolic fitness, sleep and regenerative strategies, hearing & neurosensory protection, minimising environmental toxins, and the psycho-biological factors including mental health and social connection.

Dr Robin Brown, Dr Jack Kreindler

Further reading

Eric Topol: Spotlight on the Shingles Vaccine (again) (Ref. 19)

https://erictopol.substack.com/p/spotlight-on-the-shingles-vaccineagain

Eric Topol: The Shingles Vaccine and Reduction in Dementia (Ref. 20)

https://erictopol.substack.com/p/the-shingles-vaccine-and-reduction

Alzheimer's Society: Why is dementia different for women? (Ref. 21)

https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/blog/why-dementia-different-women

References

Core dementia / epidemiology

1. Eyting M, et al. A natural experiment on the effect of herpes zoster vaccination on dementia. Nature. 2025;641:438–446.

2. Pomirchy M, et al. Herpes Zoster Vaccination and Dementia Occurrence. JAMA. 2025;333(23):2083–2092. doi:10.1001/jama.2025.5013

3. Pomirchy M, et al. Herpes zoster vaccination and incident dementia in Canada: an analysis of natural experiments. The Lancet Neurology. 2026;25(2):170–180. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(25)00455-7

4. Wang Z, et al. Herpes simplex virus 1 accelerates the progression of Alzheimer’s disease by modulating microglial phagocytosis and activating NLRP3 pathway. J Neuroinflammation. 2024;21:176.

5. Fulop T, et al. Can an Infection Hypothesis Explain the Beta Amyloid Hypothesis of Alzheimer’s Disease? Front Aging Neurosci. 2018;10:224.

6. Bukhbinder AS, et al. Do vaccinations influence the development of Alzheimer disease? Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2023;19:2216625.

7. Curran D, et al. Healthy ageing: Herpes zoster infection and the role of zoster vaccination. NPJ Vaccines. 2023;8:184.

8. Boutry C, et al. The Adjuvanted Recombinant Zoster Vaccine Confers Long-Term Protection Against Herpes Zoster: interim results of an extension study of ZOE-50 and ZOE-70. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74(8):1459–1467. doi:10.1093/cid/ciab629

9. Strezova A, et al. Final analysis of the ZOE-LTFU trial to 11 years post-vaccination: efficacy of the adjuvanted recombinant zoster vaccine against herpes zoster and related complications. eClinicalMedicine. 2025. (PubMed listing: Ref. 16)

Shingrix vs Zostavax / dementia association

10. Taquet M, Dercon Q, Todd JA, Harrison PJ. The recombinant shingles vaccine is associated with lower risk of dementia. Nat Med. 2024;30:2777–2781.

Systematic Review

11. Shah S, et al. Herpes zoster vaccination and the risk of dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. 2024;14:e3415.

Guidelines / safety

12. CDC. Shingles (Herpes Zoster) Vaccine Recommendations (Shingrix). (Updated July 26, 2024.)

13. NHS. Shingles vaccine: eligibility and schedule.

14. UK Government (shingles immunisation programme guidance for healthcare practitioners). Eligibility cohorts and dosing intervals.

15. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Warning about Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) to be included in Shingrix prescribing information. (March 2021.)