Can we believe the headlines: Why exercise isn’t much help if you are trying to lose weight

I was sent this eye-catching headline from a magazine this month. Many people struggle to lose weight and cycle through different diets, exercise routines, fads and more in an effort, amongst many other drivers, to improve their health. Is this headline true, and if not, what harm can it do when attempting to catch a reader’s attention?

While the headline is technically accurate regarding scale weight, it offers dangerous advice for long-term health. It paints a misguided picture of exercise to those at an impressionable stage in their health or weight loss journey. The key takeaway is that exercise alone rarely drives large weight loss, but it can protect muscle, improve body composition, and reduce health risks while you diet, so it should absolutely be seen as a core component of an optimal weight loss intervention. Certain types of exercise, in contrast to the headline, amplify the efficacy of a programme to lose weight.

The main problem here is not that the reported science is wrong, but that the way it is presented gives the wrong signal, and with the new weight loss medications available, that is more concerning now than ever. It is a signal that matters to a significant number of individuals.

What did the reference study show?

The authors tested a specific question: when we move more, do we burn calories in a 1:1 ratio, or does the body compensate by saving energy elsewhere? It was not itself a randomised clinical trial or meta-analysis but a modelling and synthesis paper. They identified 21 cohorts across the intervention studies, totalling 450 participants [1].

They found that in aerobic exercise trials, participants only burned about 30% of the additional calories predicted by standard models, however, resistance training cohorts often showed negative compensation, meaning that the total energy expenditure rose more than would have been predicted. Importantly, they focused on how the body adjusts its energy use, not on weight loss, fat loss or waist circumference, and indeed noted that total energy expenditure was unrelated to weight loss.

Key limitations of the study are that this is only looking at 450 individuals and out of 21 cohorts, only 3 include resistance training. Some critics also discuss the concept of exercise substitution whereby the prescribed, measured exercise might substitute other activities such as gardening [2]. This suggests the 'compensation' might not be biological, but behavioral - people simply doing less throughout the day because they tired themselves out exercising.

What does the wider body of evidence actually show?

It is true, exercise does tend to produce smaller weight loss than people expect. This is not new information. The concept of compensatory (possibly survival) mechanisms that kick-in when we attempt to lose weight has been around since the 1950s when the renown Ancel Keys wrote about the biology of human starvation [3].

That there is a behavioural change in non-intentional activity (officially called non-exercise activity thermogenesis or NEAT), such as fidgeting, when there are changes in caloric intake was first suggested 1999 [4].

All exercise is not the same: aerobic versus resistance

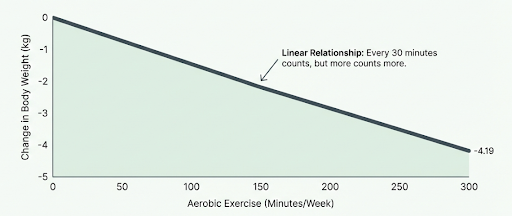

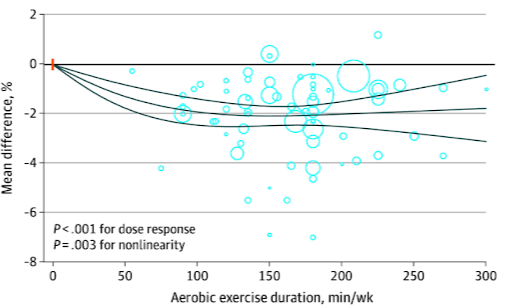

Aerobic exercise is painted as an ineffective tool for weight loss in the article, yet meta-analytical work, looking at 116 randomised clinical trials and 6880 individuals, has highlighted that there is a linear dose-response with increasing duration of aerobic exercise to 300 minutes per week resulting in a linear decrease in body weight, waist circumference and body fat [5].

Fig. The linear relationship between aerobic exercise duration and body weight. Adapted from [5]

Fig. Dose-response relationship between fat percentage and aerobic exercise duration. Source: [5]

Per additional 30 minutes per week, weight dropped by 0.52kg. At 300 minutes per week, this was an average of 4.19kg.

It’s very easy to fall into the trap of looking at total body weight as the goal we’re chasing. Weighing scales are normally body weight only, but as technology advances and drops in cost, bioimpedance scales that include measures of body composition are increasingly accessible.

Weight is not the same as body composition. Resistance training is an essential component of an exercise plan to increase and maintain muscle mass and function. If an exercise plan resulted in a neutral change in body weight but a significant drop in body fat, and thus a proportional increase in muscle mass, that would absolutely be a successful intervention even though no weight was lost.

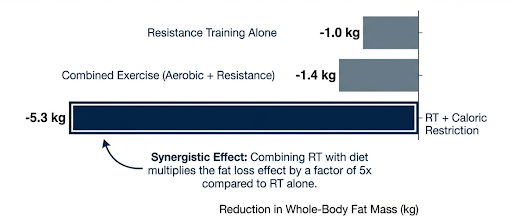

That concept aside, more systematic and meta-analytical work across 114 trials demonstrated that resistance-based exercise programmes are effective when combined with reducing calorie intake [6]. Specifically, resistance training alone was, as expected, the most effective for increasing muscle mass, whilst during dieting, the combination of both caloric restriction and resistance training was effective for maintaining muscle mass, and combined resistance and aerobic exercise during caloric restriction resulted in the most effective reduction in internal and subcutaneous body fat.

Fig. Reductions in whole-body fat mass by intervention [6]

So, whilst the scales may not move as far as expected, relying on the scales to tell the full picture of the benefits of incorporating exercise into weight loss plans is naive. Tracking waist circumference, strength, and body composition is where the real outcomes lie. No weight loss does not equal no progress.

“Sarcopenic obesity”: the hidden risk when weight loss becomes the only metric

Sarcopenic obesity is the coexistence of excess fat mass with low muscle mass or low muscle function. Muscle is not just a cosmetic tissue. It drives strength, gait speed, power, glucose disposal, and injury tolerance - a reflex to prevent a trip converting to a fall; a cushion for if we do fall. Sarcopenic obesity is associated with increased risk of death and other health issues [7], [8].

Loss of muscle mass as a result of reducing calorie intake becomes a critical health risk, especially in the new era of readily available incretin mimetic drugs, the GLP-1 and other weight loss drugs such as Mounjaro and Wegovy. Whilst there is still a debate as to whether these drugs themselves accelerate muscle loss during their use, research suggests this is on parity to that lost through calorie restriction alone [9], [10]. Thus the muscle loss is not necessarily an effect of the drug itself over and above the effectiveness in inducing caloric restriction.

This highlights the importance of maintaining a resistance training programme when reducing calories, especially when through such an efficacious intervention such as weight loss injections like Mounjaro, Wegovy and retatrutide.

Further than body composition

Even putting body composition to the side, there are wider reaching reasons to include exercise in a weight loss programme. A meta-analysis last year found that, across 97 studies, exercise added to weight-loss diet significantly improved blood sugar levels, insulin levels, insulin sensitivity, triglycerides, high-density cholesterol, and blood pressure compared to diet alone [11].

As I discussed last week (The Race Against Time), VO2peak is one of the most powerful biomarkers we have. Another systematic review and meta-analysis last year demonstrated that individuals who were overweight-but-fit, and even obese-but-fit, had no statistically significant difference in cardiovascular or all-cause mortality rates compared to normal weight-fit individuals [12]. This doesn’t mean weight doesn’t matter. It does mean that fitness is a major risk modifier that body weight alone doesn’t capture.

What does this mean for trying to lose weight and exercise?

The decision is not a binary “exercise or diet”, nor is it that if you exercise whilst trying to lose weight, you’re wasting your time.

The real decisions are:

What outcome are you optimising for?

What metrics will you track?

The common error is body weight scale fixation. Scale weight changes slowly. It also fluctuates with glycogen, gut content, and water. If you want clearer markers of progression, you need better markers.

Practical takeaways

Treat diet as the primary lever for scale weight. Use exercise as the primary lever for body composition, fitness, and adherence.

Measure more than weight. At a minimum, track waist circumference weekly, and strength performance. If available, body composition adds more granularity.

If you restrict calories, prioritise resistance training. The evidence supports better fat loss with lean mass preservation when resistance training sits alongside caloric restriction.

Expect compensation, then design around it. Plan for appetite shifts and reduced background movement in some people. Do not treat hunger as a personal failure.

Use aerobic work to target waist and fitness, not just “calories burned”. The dose response evidence suggests more minutes generally produces more effect on weight and waist, up to around 300 minutes per week in trials.

Define success as risk reduction plus capability. Fitness shifts mortality risk even when BMI stays high.

Avoid the headline trap. If a headline makes you want to stop moving, treat that as a red flag about the headline, not about exercise.

FAQs

Is exercise useless for weight loss?

No. Trials show weight loss and waist reduction with aerobic exercise, with a dose response. But the average effect is modest, and compensation can blunt it.

Why does the scale not move when I train more?

Your body can compensate through appetite, reduced non exercise movement, or water shifts. Resistance training can also increase lean mass while you lose fat, which can flatten scale change.

Should I lift weights when dieting?

Yes, in most people it is an essential component. Resistance training plus caloric restriction shows strong fat loss and preserves lean mass. Preserving lean mass matters for function and for reducing the risk of sarcopenic obesity with age.

If weight loss is slow, should I stop cardio?

Not automatically. Aerobic exercise improves waist, fitness, and cardiometabolic risk markers, even when weight change is modest.

Does the body “adapt” so exercise stops burning calories?

To a degree. While individual responses vary, the body often defends against weight loss. Plan for this compensation rather than assuming exercise is useless.

Further Reading

[1] H. Pontzer and E. T. Trexler, ‘The evidence for constrained total energy expenditure in humans and other animals’, Curr. Biol., vol. 0, no. 0, Feb. 2026, doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2026.01.025.

[2] D. Thompson, M. Del Angel, M. A. Nunes, J. T. Gonzalez, J. A. Betts, and O. J. Peacock, ‘Physical activity substitution: An overlooked constraint on energy expenditure during exercise and physical activity interventions’, Diabetes Obes. Metab., vol. 27, no. 11, pp. 6682–6690, Nov. 2025, doi: 10.1111/dom.70079.

[3] W. M. Krogman, ‘The Biology of Human Starvation. By Ancel Keys, Josef Brožek, Austin Henschel, Olaf Mickelsen, and Henry Longstreet Taylor; with the assistance of Ernst Simonson, Angie Sturgeon Skinner, and Samuel M. Wells. In two volumes, xxxii + 1385 pp.; 158 figs.; 565 tables. Univ. of Minn. Press, 1950. $25.00’, Am. J. Phys. Anthropol., vol. 10, no. 2, pp. 229–233, 1952, doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330100222.

[4] J. A. Levine, N. L. Eberhardt, and M. D. Jensen, ‘Role of Nonexercise Activity Thermogenesis in Resistance to Fat Gain in Humans’, Science, vol. 283, no. 5399, pp. 212–214, Jan. 1999, doi: 10.1126/science.283.5399.212.

[5] ‘Aerobic Exercise and Weight Loss in Adults: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis | Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise | JAMA Network Open | JAMA Network’. Accessed: Feb. 13, 2026. [Online]. Available: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamanetworkopen/fullarticle/2828487

[6] P. Lopez et al., ‘Resistance training effectiveness on body composition and body weight outcomes in individuals with overweight and obesity across the lifespan: A systematic review and meta-analysis’, Obes. Rev. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes., vol. 23, no. 5, p. e13428, May 2022, doi: 10.1111/obr.13428.

[7] E. Benz et al., ‘Sarcopenia and Sarcopenic Obesity and Mortality Among Older People’, JAMA Netw. Open, vol. 7, no. 3, p. e243604, Mar. 2024, doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.3604.

[8] S. Mirzai, S. Carbone, J. A. Batsis, S. B. Kritchevsky, D. W. Kitzman, and M. D. Shapiro, ‘Sarcopenic Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: An Overlooked but High-Risk Syndrome’, Curr. Obes. Rep., vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 532–544, Sep. 2024, doi: 10.1007/s13679-024-00571-2.

[9] M. Look et al., ‘Body composition changes during weight reduction with tirzepatide in the SURMOUNT‐1 study of adults with obesity or overweight’, Diabetes Obes. Metab., vol. 27, no. 5, pp. 2720–2729, May 2025, doi: 10.1111/dom.16275.

[10] D. Willoughby, S. Hewlings, and D. Kalman, ‘Body Composition Changes in Weight Loss: Strategies and Supplementation for Maintaining Lean Body Mass, a Brief Review’, Nutrients, vol. 10, no. 12, p. 1876, Dec. 2018, doi: 10.3390/nu10121876.

[11] S. Soltani et al., ‘The Effect of Aerobic or Resistance Exercise Combined With a Low-Calorie Diet Versus Diet Alone on Cardiometabolic Outcomes in Adults with Overweight and Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis’, Nutr. Rev., p. nuaf065, Jun. 2025, doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuaf065.

[12] N. R. Weeldreyer, J. C. De Guzman, C. Paterson, J. D. Allen, G. A. Gaesser, and S. S. Angadi, ‘Cardiorespiratory fitness, body mass index and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis’, Br. J. Sports Med., vol. 59, no. 5, p. e108748, Nov. 2024, doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2024-108748.