Building Muscle What Wins: Vegan or Omnivorous Diets?

There is a persistent belief in the fitness culture that animal protein is required for optimal muscle growth.

And a second belief that if you do not distribute protein perfectly across the day, you will blunt your training gains.

A tightly controlled feeding study published a few months ago just tested both assumptions.

In 40 healthy, resistance-trained young adults consuming 1.1 to 1.2 g/kg/day of protein for 9 days, there was no difference in the rate of new muscle protein formation between omnivorous and vegan dietary patterns. The balance of how that protein was spread across meals in a day also made no difference [1].

Before this gets into diet wars, let’s look carefully at what was tested and what it means.

What the study actually did

Design: this was a short controlled feeding intervention with resistance training over 9 days. The 40 participants were aged on average 25 yo.

Protein intake was 1.1 to 1.2 g/kg/day and calories were calculated for weight maintenance. Their diets were either omnivorous or vegan and their protein was either equally distributed across three meals or distributed in an unbalanced pattern of 10%, 30%, 60% across three meals. They trained three times per week.

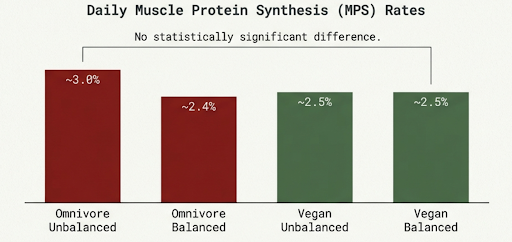

Result: daily new muscle protein formation was:

There were no statistically significant differences between the groups.

The authors therefore conclude that at moderate protein intake, under resistance training conditions, vegan and omnivorous patterns stimulated similar daily muscle protein synthesis and that the protein distribution pattern did not meaningfully alter the rate either.

Why should this matter if you’re not vegan?

Two common assumptions get tested here.

1. “Plant protein cannot match animal protein”

Short term feeding studies show whey protein generates a strong initial muscle protein formation response due to rapid leucine (an amino acid) delivery [2].

However, acute 2-3 hour responses do not always predict a 24 hour pattern of muscle protein formation.

This trial measured daily new muscle protein formation and found no difference between animal-based and plant based diets at sufficient total protein intake.

That aligns with systematic reviews suggesting plant-based diets can support similar muscle strength and performance outcomes to omnivorous diets when total protein is adequate [3].

It does not mean all proteins are equivalent gram-for-gram.

It suggests total intake and training stimulus are the greater determinants in young adults.

2. “Protein must be evenly distributed to maximise gains”

The idea that protein should be “balanced” across meals came from acute tracer studies that measure muscle protein formation over a short window after eating. In one classic post-resistance exercise study, muscle protein formation rose with protein intake then plateaued, with around 20 g maximising muscle protein formation over the next few hours in young men. Extra amino acids beyond that dose were more likely to be broken down and used as fuel rather than further increasing muscle growth in that short measurement window [4].

From this came the hypothesis that spreading protein evenly across the day would create multiple near maximal muscle protein formation “peaks”, and therefore produce more total anabolic (growth) signalling than concentrating most protein into one meal.

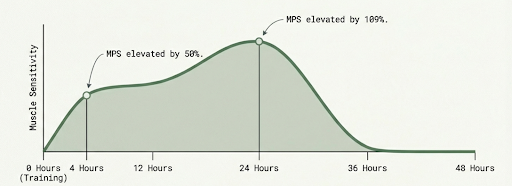

Where this model falls down is assuming that looking at a few-hour window predicts what happens across the whole day. Resistance exercise creates a long anabolic window of growth. Muscle protein formation remains elevated even at 24 hours following resistance training and returns toward baseline by around 36 hours [5]. Notably, muscle protein formation was elevated by 50% at 4 hours, and by 109% at 24 hours following heavy resistance exercise.

Fig. Rates of muscle protein synthesis (MPS) following resistance training. Adapted from [5].

That means muscle is not responding for just a few hours after a meal. It remains in an increasingly elevated, repair-oriented state for most of the following day.

So the relevant window is not only the 2 to 4 hours after a meal, it is the full recovery period. If muscle remains in an anabolic, amino acid sensitive state for much of the day after training, then precise protein distribution across meals in a 24 hour window may matter less than total daily protein and a repeated training stimulus.

That is exactly what this study observed: daily muscle protein synthesis did not differ between omnivorous and vegan patterns, and it did not differ between balanced and unbalanced distribution when total intake was held at 1.1 to 1.2 g/kg/day with resistance training.

Where a little caveat is required

This was:

9 days

Young adults

Energy balanced

Moderate protein intake

Resistance training stimulus

It did not test:

Older adults

Caloric deficit

Long-term hypertrophy

Elite training level of volume

Older adults can show anabolic (growth) resistance and may require higher per-meal protein doses but some studies demonstrate that there is a reasonably similar muscle protein formation response [6].

The Bigger Question: What Happens to Long-Term Health If You Swap Some Animal Protein for Plant Protein?

This is where this conversation deviates from the polarising diet wars of whether to be vegan or carnivore, and opens a more relevant and interesting conversation.

If muscle protein synthesis is similar at adequate intake, regardless of plant or animal origin (assuming both are of quality sources), what are the broader health implications of substituting some animal protein with plant protein?

This is where the evidence becomes more consequential for overall wider health goals, whilst still maintaining performance.

Cancer risk

The International Agency for Research on Cancer classifies processed meat as carcinogenic to humans (Group 1) with sufficient evidence for colorectal cancer, and red meat as probably carcinogenic (Group 2A) [7].

This classification reflects strength of evidence, not magnitude of individual risk.

It does not mean moderate consumption inevitably causes cancer.

It does mean the evidence linking processed meat to colorectal cancer meets high causality standards.

Cardiovascular risk and atherogenic particles

Meta-analysis of randomised, controlled trials shows vegetarian and vegan diets reduce LDL cholesterol and ApoB compared with omnivorous diets [8].

ApoB is clinically relevant because it reflects atherogenic (the harmful effect of cholesterol that leads to heart disease) potential, often more predictively than LDL cholesterol when the two are discordant (when the two metrics reflect a differing risk prediction).

Lower ApoB means lower circulating atherogenic particle burden.

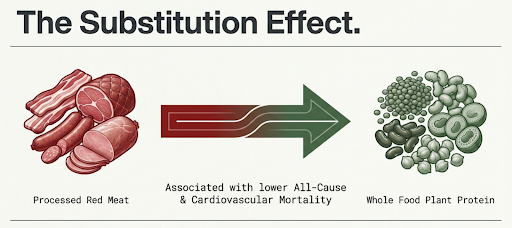

Mortality and protein substitution

Large cohort analyses consistently show lower all-cause and cardiovascular mortality when plant protein replaces certain animal proteins, particularly processed red meat [9], [10].

Many of these are observational studies, so residual confounding remains possible. But the substitution signal is consistent: replacing processed red meat with plant protein associates with lower all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

The Balanced Conclusion

This trial suggests that at 1.1 to 1.2 g/kg/day protein in young resistance-trained adults:

Vegan and omnivorous diets stimulate similar rates of daily muscle protein synthesis

Protein distribution is less critical than total intake

Resistance training remains the primary anabolic signal

The broader literature suggests:

Swapping some processed red meat for whole-food plant proteins associates with lower colorectal cancer risk

Plant-rich diets reduce LDL cholesterol and ApoB

Replacing certain animal proteins with plant proteins associates with lower mortality in cohort data

What this does not mean:

Animal protein is inherently harmful

All plant proteins are equal

Ultra-processed plant substitutes carry identical benefits

Older adults respond the same way

Protein intake is irrelevant

It is, therefore, still possible to enjoy animal protein, but substitute some animal protein with whole-food plant protein, and maintain adequate total protein intake, continue resistance training, and likely retain the muscle-building potential while potentially improving long-term cardiometabolic and cancer risk markers.

FAQs

1. Does this study prove vegan diets build the same muscle as omnivorous diets?

No. It did not measure hypertrophy.

It measured daily myofibrillar protein synthesis over 9 days, under controlled feeding and resistance training.

It shows similar daily muscle protein formation between vegan and omnivorous patterns at 1.1 to 1.2 g/kg/day in young adults.

That is supportive, not definitive, for long-term muscle gain.

2. If distribution did not matter here, can I eat all my protein in one meal?

Not necessarily.

This study compared balanced versus skewed patterns, not extreme one-meal-per-day scenarios.

It suggests you do not need perfect symmetry across meals. It does not prove that very low-frequency feeding is equivalent under all conditions.

3. Why did earlier studies suggest spreading protein out was important?

Because muscle protein synthesis plateaus after a moderate protein dose at rest, and extra amino acids are more likely to be broken down and used for energy rather than increasing muscle protein formation further.

From that came the idea that multiple moderate doses might stimulate more total synthesis than one large bolus.

But resistance exercise extends the anabolic window and increases amino acid sensitivity for up to 24 hours.

That changes the practical importance of exact distribution.

4. Would the findings be the same in older adults?

Uncertain.

Some studies in older adults show anabolic resistance and often require higher per-meal protein doses to maximise muscle protein formation while others do not.

This study involved young adults. It does not directly answer the question for people in their 60s or 70s.

5. Does this mean protein timing does not matter at all?

No.

It suggests that when total intake is adequate and resistance training is present, distribution may be less critical than once believed in young adults.

Timing may still matter in energy deficit, in older adults, or in high-volume elite training contexts.

6. If plant protein is sufficient for muscle, why do some athletes struggle on vegan diets?

Common reasons include:

Total protein intake drifting lower

Energy intake dropping unintentionally

Lower leucine density requiring larger portions

Reduced convenience leading to lower compliance

The muscle physiology does not appear fragile at adequate intake. Adherence and total intake are often the limiting factors.

7. What about cancer and cardiovascular risk?

Processed meat is classified as carcinogenic for colorectal cancer, and red meat as probably carcinogenic, based on strength of evidence.

Vegetarian and vegan dietary patterns lower LDL cholesterol and ApoB in randomised trials.

Observational studies suggest replacing processed red meat with plant protein associates with lower all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

This does not prove causation in every context. It supports a cautious substitution model.

8. How much protein should a resistance-trained adult aim for?

This study used 1.1 to 1.2 g/kg/day and observed no difference between dietary patterns.

Sports nutrition consensus statements often recommend 1.2 to 1.6 g/kg/day for active individuals depending on training load and goals.

The exact number depends on age, energy balance, and training volume.

9. Does this mean high protein intakes are unnecessary?

For sedentary adults, average intake in high-income countries often already meets or exceeds the RDA.

For resistance-trained adults, adequate protein supports adaptation. More is not always better, but too little will limit progress.

The question is not “maximise protein.”

It is to meet the requirement that matches your training goals and age.

10. What is the simplest takeaway?

If you train hard and hit sufficient total protein, your muscle appears robust to reasonable variation in protein source and meal distribution.

The bigger risks to long-term health may lie in diet quality, cardiometabolic markers, and recovery behaviours rather than whether your protein came from whey or lentils.

The real lever is adequacy plus consistency.

Further Reading

[1] A. T. Askow et al., ‘Impact of Vegan Diets on Resistance Exercise-Mediated Myofibrillar Protein Synthesis in Healthy Young Males and Females: A Randomized Controlled Trial’, Med. Sci. Sports Exerc., vol. 57, no. 9, pp. 1923-1934, Sep. 2025, doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000003725.

[2] J. E. Tang, D. R. Moore, G. W. Kujbida, M. A. Tarnopolsky, and S. M. Phillips, ‘Ingestion of whey hydrolysate, casein, or soy protein isolate: effects on mixed muscle protein synthesis at rest and following resistance exercise in young men’, J. Appl. Physiol., vol. 107, no. 3, pp. 987-992, Sep. 2009, doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00076.2009.

[3] R. J. Reid-McCann, S. F. Brennan, N. A. Ward, D. Logan, M. C. McKinley, and C. T. McEvoy, ‘Effect of Plant Versus Animal Protein on Muscle Mass, Strength, Physical Performance, and Sarcopenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials’, Nutr. Rev., vol. 83, no. 7, pp. e1581-e1603, Jul. 2025, doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuae200.

[4] D. R. Moore et al., ‘Ingested protein dose response of muscle and albumin protein synthesis after resistance exercise in young men’, Am. J. Clin. Nutr., vol. 89, no. 1, pp. 161-168, Jan. 2009, doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26401.

[5] J. D. MacDougall, M. J. Gibala, M. A. Tarnopolsky, J. R. MacDonald, S. A. Interisano, and K. E. Yarasheski, ‘The Time Course for Elevated Muscle Protein Synthesis Following Heavy Resistance Exercise’, Can. J. Appl. Physiol., vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 480-486, Dec. 1995, doi: 10.1139/h95-038.

[6] T. B. Symons, S. E. Schutzler, T. L. Cocke, D. L. Chinkes, R. R. Wolfe, and D. Paddon-Jones, ‘Aging does not impair the anabolic response to a protein-rich meal’, Am. J. Clin. Nutr., vol. 86, no. 2, pp. 451-456, Aug. 2007, doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.2.451.

[7] ‘IARC Monographs evaluate consumption of red meat and processed meat’.

[8] C. A. Koch, E. W. Kjeldsen, and R. Frikke-Schmidt, ‘Vegetarian or vegan diets and blood lipids: a meta-analysis of randomized trials’, Eur. Heart J., vol. 44, no. 28, pp. 2609-2622, Jul. 2023, doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad211.

[9] M. Song et al., ‘Association of Animal and Plant Protein Intake With All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality’, JAMA Intern. Med., vol. 176, no. 10, pp. 1453-1463, Oct. 2016, doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.4182.

[10] S. Naghshi, O. Sadeghi, W. C. Willett, and A. Esmaillzadeh, ‘Dietary intake of total, animal, and plant proteins and risk of all cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies’, BMJ, vol. 370, p. m2412, Jul. 2020, doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2412.