Why Exercise "Intensity" Matters More Than We Thought

A new 2025 study challenges the old rules of exercise, suggesting that 1 minute of vigorous activity could be worth up to 9 minutes of moderate effort for your health[1]. Here is how to balance this new information with exercise training zones.

Cardiorespiratory fitness is one of the strongest predictors of long-term health. It outperforms cholesterol, blood pressure, and even smoking status as a marker of future risk[2].

Improving cardiorespiratory fitness involves moderate to vigorous intensity activity. For years, a golden rule of public health was simple: every minute of vigorous exercise (like running) was worth two minutes of moderate exercise (like brisk walking). It was a neat 1:2 ratio.

However, this study, in Nature Communications, has disrupted that assumption. By analysing data from over 73,000 people, researchers found that the relationship isn't linear. In fact, depending on the health outcome, one minute of vigorous activity can provide the same risk reduction as 3.5 to 9.4 minutes of moderate activity.

This doesn't mean moderate exercise is useless. But it does mean that if you are time-poor, the intensity of your time spent matters.

What does this mean for training zones? Below I break down what this means for different zones of training and how they change your physiology, and how to build a protocol tailored to your health, whether as an aspiring athlete, or managing blood pressure, prediabetes, or liver health.

The 5 Zones: A Quick Primer

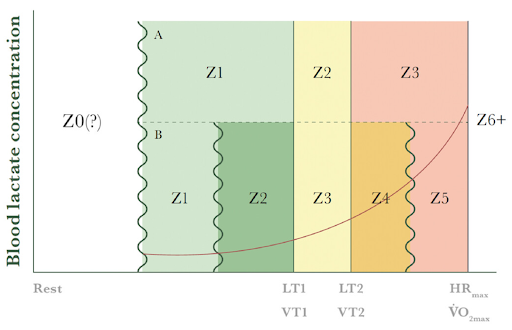

To understand the science, we need to define "zones." Many physiologists divide exercise into five zones based on your heart rate (HR) and effort, however, some use 3 or 4 zones.

Figure 1. Training zone definitions. Source: [3]

• Zone 1 (Recovery): Very light. <60% Max Heart Rate.

• Zone 2 (The Aerobic Base): 60–70% Max HR. You can hold a conversation, but it requires some focus. The body primarily utilises fat as the fuel.

• Zone 3 (The Grey Zone): 70–80% HR. Breathing deepens; conversation becomes broken.

• Zone 4 (Threshold): 80–90% HR. "Comfortably hard." You can only sustain this for 20–40 minutes.

• Zone 5 (Max Effort/HIIT): >90% HR. All-out sprints. Sustainable for only seconds to a few minutes.

What the paper showed

The researchers used wearable physical activity data from a large UK Biobank cohort and linked it to later health outcomes over years of follow up.

They modelled dose response curves for different intensities, then calculated “equivalent minutes” of moderate versus vigorous activity for outcomes including:

all cause mortality

cardiovascular mortality

major adverse cardiovascular events

type 2 diabetes

The findings were that for moderate intensity, the equivalence to 1 min of vigorous intensity was:

4.1 minutes for all cause mortality

7.8 minutes for cardiovascular mortality

5.4 minutes for major adverse cardiovascular events

9.3 minutes for type 2 diabetes

So the “value” of a vigorous minute looked more like 4 to 9 moderate minutes, not 2.

Does this mean we should drop zone 2 and focus more on zone 5?

It’s easy to jump to this conclusion but this paper did not study zone 2 versus zone 5 training.

It studied accelerometer inferred intensity.

That means the wearable devices classified intensity from movement signals, not from lab-based CPEX data on ventilatory thresholds, lactate testing, or VO₂peak. So something like a hard stair climb, a fast walk uphill, or carrying heavy bags could classify as “vigorous” without resembling HIIT training or knowing what the underlying physiology was sufficient to see the adaptations from zone 5 training.

So the simple conclusion is more limited: at a population level, higher movement intensity is associated with steeper risk reductions for several outcomes. Think of this including activities that also classify as VILPA (https://wellfounded.health/insights/vilpa-the-secret-to-a-longer-life-could-be-in-your-daily-routine)

So how does this adjust zone 2 and zone 5 recommendations?

Zone 2 still builds the base that lets you tolerate the hard work at higher intensity. It is not an “either or”.

You recover better.

You tolerate more weekly volume.

You reduce injury risk.

You make the hard sessions possible.

Having a strong aerobic base allows faster recovery between cardio and weights sessions. It builds capillary density (the tiny blood vessels feeding your muscles) by ~15%, significantly improving your ability to burn fat as fuel and clear lactate at the higher intensities[4].

It helps you accumulate work and build mitochondria (almost as effectively as vigorous intensity - 23 vs 27%) with less recovery time.

Zone 5 vigorous work still acts like a multiplier.

It tends to improve cardiorespiratory fitness faster, and fitness itself correlates strongly with long term outcomes.

High intensity acts as a potent signal to the body. While zone 2 builds mitochondria slowly, Sprint Interval Training (zone 5) has been found to be ~3.9 times more efficient at boosting mitochondria per hour of exercise compared to zone 2[4].

So What Split Should You Do?

One size does not fit all. Context really does matter here. What are the risks of leaning too hard into zone 5?

1. The Time Efficiency - Recovery Trade-off

For reducing cardiovascular mortality risk, vigorous activity is exponentially more potent.

But zone 5 creates a large systemic stress. Not just muscular. Neural, autonomic, endocrine, and inflammatory.

In isolation, this creates adaptation. Combine it with the underlying cause of time scarcity, high workload, and it compounds. Large sympathetic activation; cortisol and catecholamine spikes; central fatigue via neurotransmitter depletion; sleep fragmentation if sessions are late or frequent.

2. Sympathetic activation

When a zone 2 / 5 is balanced well, we see the stress of zone 5 - reflected in the low HRV, decreased parasympathetic tone, disturbed sleep - recover before the next session, a concept known as hormesis (when a low dose of a stressor causes adaptation and increases resilience). A hormetic stressor will compound other stressors, so while in the short term VO2peak might increase, HRV balance may worsen, infection rates increase, sleep quality deteriorate etc.

3. Injury Risk

Zone 5 concentrates mechanical and connective tissue stress.

When total volume is low, tissues are under-conditioned and a high-volume of vigorous movement risks injury with our proper conditioning. Common patterns:

Achilles and patellar tendinopathy

Calf and hamstring strains

Lumbar overload in cyclists and rowers

Recurring minor injuries that interrupt consistency

Short programmes, as often utilised in research, tolerate this but this is particularly relevant for those in a predominantly desk-based job, high life load or poor recovery due to suboptimal sleep, including jet lag.

4. Behavioural sustainability

Vigorous intensity is hard. Really hard. If you’ve never seen yourself slumping off the bike or rower, collapsing to the floor at the end of the session, you’ve probably not been right to the top of your engine.

It’s not just physiologically hard; it’s psychologically hard.

In the early days, seeing the acute benefits is motivating. When work stress peaks, things change for a lot of people. High intensity sessions are the first to drop and consistency disappears.

5. Specific health goals:

Further nuance lies in tailoring the split to optimise underlying health vulnerabilities.

Insulin Resistance or Prediabetes: the goal is to lower blood sugar and improve insulin sensitivity. Skeletal muscle is a "glucose sink" so resistance training must certainly form part of the training plan. For the cardio split, a 2025 review found that while both moderate and high-intensity exercise lower A1c, HIIT improved the Insulin Sensitivity Index significantly more than moderate training. Intensive lifestyle intervention (diet + exercise) has been shown to reduce the progression to type 2 diabetes by 58% but it must be sustainable.

Fatty Liver (MASLD/NAFLD): Exercise alone can reduce liver fat by 20–30%[5]. Volume is key. For liver fat, total energy burn matters most.

Blood pressure and vascular ageing: both moderate and interval training reduce blood pressure. A recent meta analysis comparing high intensity interval training with moderate continuous training found both improved BP, with interval training showing a slightly larger reduction in some analyses.

Exercise does not happen in a vacuum.

Consistency beats intensity.

To get the right balance, cardio split must be seen as one tenet of exercise physiology. Don’t neglect:

1. Sleep: You do not get fitter while you train; you get fitter while you sleep. Aim for 7–9 hours.

2. Nutrition: For metabolic health, time your carbohydrates around your high-intensity sessions (Zones 4/5) when your muscles are ready to soak them up.

3. Resistance Training Cardio builds the engine; strength builds the chassis. Skeletal muscle is your body's largest "glucose sink," helping to control blood sugar independent of aerobic fitness.

4. Mobility & Stability You cannot safely express high power (Zone 5) on an unstable frame. Stiffness leads to injury, which slows or stops progress.

5. Periodisation Progress is not linear, and you cannot redline every day. "Periodisation" is the strategic planning of hard and easy days to avoid burnout.

The practical prescription logic:

1. Minimum effective dose

For time poor people, design the smallest plan that still contains real intensity.

2. Optimal dose

For those with the luxury of training time, keep intensity but also build volume, because volume supports durability.

3. Safety and ramp

Match intensity to risk, baseline fitness, and injury history.

FAQs

1) Did the study prove that 1 minute of vigorous exercise equals 9 minutes of moderate exercise for everyone?

No.

It estimated average “equivalence” across a large population.

The ratio changed by outcome and by the dose you compare.

2) What counted as “vigorous” in this paper?

The devices inferred intensity from wrist accelerometer signals.

That captures movement acceleration and variability.

It does not directly measure VO₂, ventilatory thresholds, or lactate.

3) Does “vigorous” here mean Zone 5 training?

Not necessarily.

A hard stair climb, fast uphill walk, carrying loads, or uneven terrain can register as vigorous.

That may not produce the same physiology as structured Zone 5 intervals.

4) Should I drop Zone 2 because vigorous minutes look more “valuable”?

No.

Zone 2 builds the base that lets you repeat high intensity safely and recover between sessions.

Most people who abandon Zone 2 end up training less overall within a few months.

5) Is Zone 3 really useless?

No.

It is just easy to drift into it without a clear purpose.

Use it deliberately for tempo work, race specific prep, or progression blocks.

6) How do I know which zone I am in without a lab test?

Use at least two anchors.

Heart rate as a percent of your observed max plus RPE, plus the talk test.

If you take beta blockers, heart rate zones often mislead, so lean more on RPE and breathing.

7) What is a practical “time poor” template that respects the paper without overdoing it?

Two sessions per week can work well for many people:

One Zone 2 session (30 to 60 minutes).

One interval session (for example 10 minute warm up, then 6 to 10 repeats of 30 seconds hard with 90 seconds easy, then cool down).

8) How often should I do Zone 5 or HIIT?

For most healthy adults, start with once per week.

Keep at least 48 hours between hard sessions.

Build consistency first, then add a second session only if recovery stays good.

9) Who should be cautious with high intensity sessions?

Anyone with cardiac symptoms, known heart disease, uncontrolled hypertension, or unexplained breathlessness, chest pain, or syncope.

Also anyone returning from injury, or starting exercise after a long gap.

In those groups, start with Zone 2 and resistance training, then progress.

10) Does more intensity increase injury risk?

Often, yes, if you ramp too fast.

The risk comes from tendon and connective tissue load, not just fitness.

Lower impact modes like cycling, rowing, ski erg, or incline walking reduce peak forces.

11) What are the early signs I am leaning too hard into intensity?

Sleep fragmentation.

Persistently reduced HRV or rising resting heart rate over a week.

Heavy legs, irritability, or repeated minor strains.

When you see these, reduce intensity or reduce frequency before you abandon training entirely.

12) Can walking count as vigorous?

Sometimes.

Uphill fast walking, stairs, or loaded carries can reach vigorous movement signals and high heart rates in many people.

For fitter people, flat walking often stays in Zone 1 to Zone 2.

13) Should I “convert minutes” using the 4 to 9 ratio?

Use it as motivation, not a calculator.

The paper does not give an individual prescription rule.

Your best constraint is recovery and repeatability across weeks.

14) If my goal is prediabetes or insulin resistance, should I prioritise intervals?

Intervals can help insulin sensitivity.

But resistance training remains non negotiable because muscle mass drives glucose disposal.

A realistic split is resistance training two to four times per week plus one interval day plus one Zone 2 day.

15) If my goal is fatty liver, should I prioritise volume instead of intensity?

Often, yes.

Total weekly energy expenditure and consistency matter a lot.

Intervals can complement this, but they rarely replace the need for steady volume.

16) If my goal is blood pressure, do I need HIIT?

Not always.

Both continuous moderate training and intervals reduce blood pressure in many studies.

Pick the approach you can sustain without sleep disruption.

17) How fast should I progress if I am new to intervals?

Change one variable at a time.

First add frequency, then add repeats, then shorten recovery, then increase effort.

A safe default is a 4 to 6 week ramp.

18) Does travel and jet lag change how I should use intensity?

Yes, in practice.

Jet lag and poor sleep often increase perceived exertion and slow recovery.

On travel weeks, keep Zone 2 and strength, and treat hard intervals as optional rather than compulsory.

Further Reading

[1] R. K. Biswas, M. N. Ahmadi, A. Bauman, K. Milton, N. A. Koemel, and E. Stamatakis, ‘Wearable device-based health equivalence of different physical activity intensities against mortality, cardiometabolic disease, and cancer’, Nat. Commun., vol. 16, no. 1, p. 8315, Oct. 2025, doi: 10.1038/s41467-025-63475-2.

[2] R. Ross et al., ‘Importance of Assessing Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Clinical Practice: A Case for Fitness as a Clinical Vital Sign: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association’, Circulation, vol. 134, no. 24, pp. e653–e699, Dec. 2016, doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000461.

[3] S. Sitko et al., ‘What Is “Zone 2 Training”?: Experts’ Viewpoint on Definition, Training Methods, and Expected Adaptations’, Int. J. Sports Physiol. Perform., vol. 20, no. 11, pp. 1614–1617, Feb. 2025, doi: 10.1123/ijspp.2024-0303.

[4] K. S. Mølmen, N. W. Almquist, and Ø. Skattebo, ‘Effects of Exercise Training on Mitochondrial and Capillary Growth in Human Skeletal Muscle: A Systematic Review and Meta-Regression’, Sports Med. Auckl. Nz, vol. 55, no. 1, pp. 115–144, 2025, doi: 10.1007/s40279-024-02120-2.

[5] J. G. Stine et al., ‘Exercise Training Is Associated With Treatment Response in Liver Fat Content by Magnetic Resonance Imaging Independent of Clinically Significant Body Weight Loss in Patients With Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis’, Am. J. Gastroenterol., vol. 118, no. 7, pp. 1204–1213, July 2023, doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000002098.