Sleep Quality Over Time Predicts Heart Risk:

New 7-year data shows up to 55% higher heart disease risk from persistently poor sleep — even when other lifestyle factors stay the same.

Sleep quality and duration are both strongly linked to the risk of cardiovascular disease.

A new 7-year prospective study, with 55,335 person-years of follow-up, has found that adults who had consistently poor sleep duration or quality had up to a 55% higher risk of developing cardiovascular disease (CVD) - heart attacks or strokes - even after adjusting for confounders like physical activity, BMI, and comorbid conditions (PMID: 40186318).

It’s easy for bad habits to creep in around work; eating late, after we get home from work and put the children to bed, going back to do just a little more work after, which then turns into a few hours. Insights into both duration and quality of sleep gives us an additional vital sign that evolves with stress, ageing, and workload.

Optimal duration and quality

This study tracked 7,905 adults aged 45 and above, following both their sleep quality and duration over an 8 year period, not just a baseline snapshot. Optimal sleep duration was 6-8 hours and poor was anything outside that window. Sleep quality was assessed by the number of days of restless sleep per week (insomnia, waking early etc). However, at baseline there was already a significantly increased risk of cardiovascular diseases for both duration (22% higher) and sleep quality (19% higher).

The following patterns of increased rates of cardiovascular risk were seen for sleep duration:

Optimal to poor: increased by 20%

Poor to optimal: still increased by 23%

Consistently poor: increased by 36%

And for sleep quality:

Optimal to poor: increased by 42%

Poor to optimal: not significantly increased

Consistently poor: increased by 55%

This was regardless of age, sex, socioeconomic status, smoking, physical activity, and depression. This association remained significant even after taking account of chronic conditions like diabetes and hypertension.

Consistency matters: how your sleep changes over years, not just how you slept last night is an important barometer of cardiovascular risk.

The “Sweet Spot”

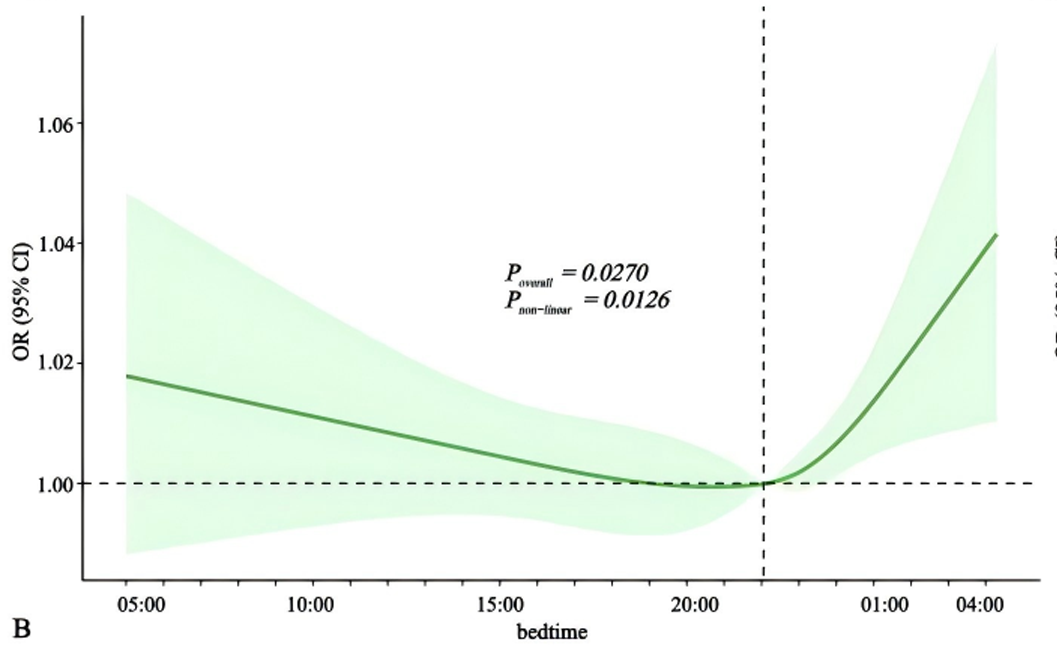

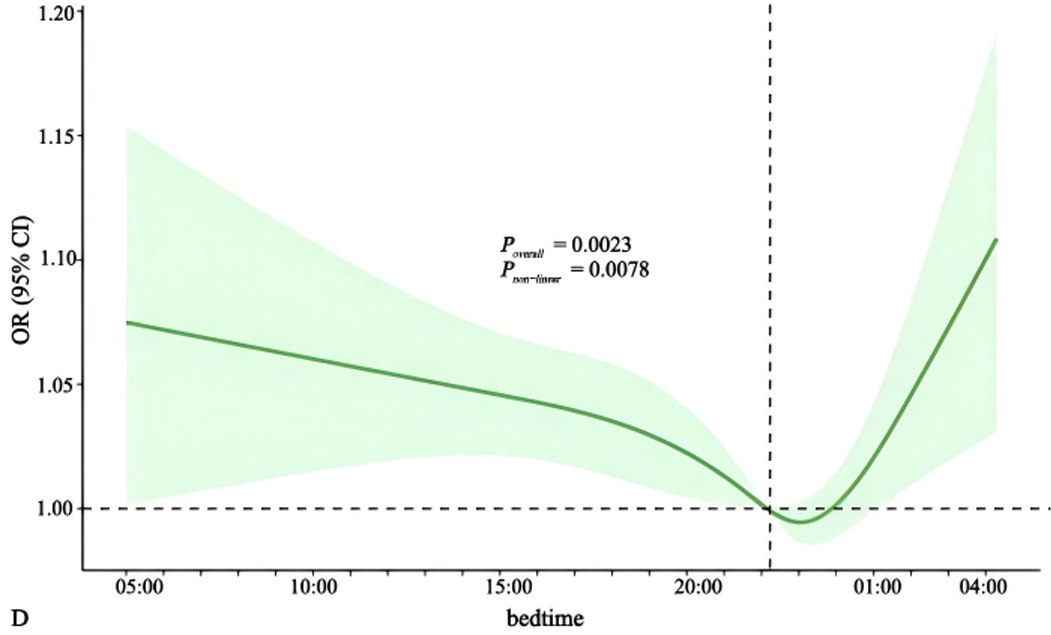

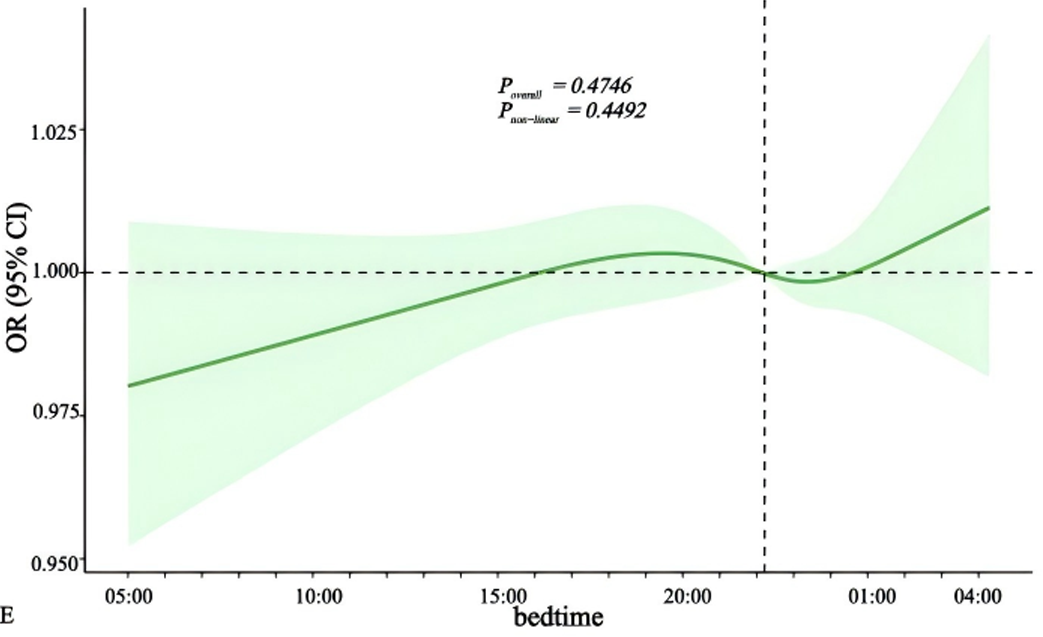

Research indicates that the time at which individuals go to bed could impact heart health, with findings suggesting that going to sleep between 10 PM and 11 PM might be optimal for reducing CVD risk: (PMID: 40644492)

Fig 1: Bedtime and heart attacks

Fig 2: Bedtime and high blood pressure

Fig 3: Bedtime and stroke

The research also highlights a U-shaped association between sleep timing and various cardiovascular outcomes. Individuals who go to bed later than midnight have been found to exhibit a higher risk of CVD compared to those who sleep at more conventional times.

Digging into the “Why?”

That poor sleep duration and/or quality is linked with CVD is consistent throughout the evidence (PMID: 37829258; PMID: 40150528). The specific mechanisms underlying this relationship remain partially understood. Underlying factors may include:

“Fight or flight” imbalance: Poor sleep suppresses the parasympathetic (rest and digest) system and elevates sympathetic (fight or flight) activity, increasing blood pressure and resting heart rate.

Poor metabolic health: Fragmented or insufficient sleep worsens insulin resistance and increases appetite, fuelling weight gain and metabolic syndrome.

Systemic inflammation: Sleep deprivation elevates markers like CRP and IL-6, contributing to atherosclerotic plaque development (that build up in the vessels of the heart and brain).

Circadian disruption: Disturbed sleep patterns impact hormonal rhythms, affecting cortisol, melatonin, and blood vessel function.

Poor cholesterol control: Late bedtimes can lead to increased levels of triglycerides and low-density lipoprotein and decreased levels of high-density lipoprotein

Ultimately, it’s not just about cardiovascular disease though. The effects of bad habits compound: individuals who sleep late are often predisposed to various cardiometabolic issues, such as obesity, diabetes, and hypertension, which all increase the risk of developing CVD. Furthermore, inadequate sleep leads to increased stress and negative mood, potentially reducing motivation for healthy behaviors such as exercise, underlining the importance of addressing both sleep patterns and stress management.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Is one bad month of sleep enough to raise heart disease risk?

A: Not likely. It’s the trajectory, persistent or worsening sleep, that appears most predictive of cardiovascular risk over time.

Q: What is the ideal amount of sleep for heart health?

A: Around 7-8 hours per night, with high sleep efficiency and consistency. Both short (<6h) and long (>9h) durations are associated with worse outcomes.

Q: How early can sleep changes predict cardiovascular issues?

A: Changes in HRV or resting heart rate often precede clinical changes in blood pressure or lipids by months or even years.

Q: Are wearables like OURA and WHOOP reliable for tracking sleep?

A: While not diagnostic tools, they’re validated for trend monitoring. Used correctly, they provide early insights into sleep quality and recovery balance.

Q: What biomarkers worsen as sleep declines?

A: hsCRP, fasting insulin, cortisol rhythms, triglycerides, and even Lp(a) expression can be impacted over time.

Q: What is the single most important sleep hygiene habit to prioritise?

A: Consistent wake-up time. Anchoring your wake time, even on weekends, helps regulate your circadian rhythm more than any other factor. It's the most potent "zeitgeber" (time cue) for your internal clock.

Q: Is it better to go to bed early even if I don’t feel tired?

A: Not necessarily. Going to bed too early can increase sleep latency and frustration, especially if you haven’t had sufficient sleep pressure (e.g. from movement or mental engagement). Target a consistent bedtime around 10-11 PM and use wind-down cues, dim lighting, stretching, low-stimulus activities, to help transition.

Q: How does caffeine affect sleep if I stop by lunchtime?

A: Caffeine has a half-life of 5-7 hours in most people, meaning residual stimulation can still affect sleep 8-10 hours later, especially for slow metabolisers. Some high performers benefit from a complete caffeine cut-off by midday. Testing a caffeine-free window for 7 days can reveal your sensitivity.

Q: Can supplements improve sleep quality?

A: In some cases. Magnesium, L-theanine, and glycine have modest evidence for improving sleep onset and quality, especially in people with suboptimal levels. But they should support, not replace, good sleep routines. Use them judiciously and cycle if needed.

Q: What should I do if I wake in the night and can’t get back to sleep?

A: Avoid clock-watching. If you're awake for more than ~20 minutes, leave the bed and engage in a quiet, non-stimulating activity (e.g. reading, breathing exercises) until drowsiness returns. This helps recondition your bed as a cue for sleep rather than frustration.

Q: How much variation in sleep time is acceptable for health?

A: Ideally, keep bedtime and wake time within a 30-60 minute window across the week. Larger swings, especially late-night catch-up on weekends, are linked with worse cardiometabolic outcomes, sometimes referred to as “social jet lag.”

Further Reading

Pan Y, Zhou Y, Shi X, He S, Lai W. The association between sleep deprivation and the risk of cardiovascular diseases: A systematic meta‑analysis. Biomed Rep. 2023 Sep 12;19(5):78. doi: 10.3892/br.2023.1660. PMID: 37829258; PMCID: PMC10565718.

Pintacom J, Pliannuom S, Buawangpong N, Angkurawaranon C, Pinyopornpanish K. The Association Between Poor Sleep Quality and Lipid Levels Among Dyslipidemia Patients in Thailand: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare (Basel). 2025 Mar 20;13(6):678. doi: 10.3390/healthcare13060678. PMID: 40150528; PMCID: PMC11941784.

Zhang X, Wang D, Liu J. Associations of sleep pattern, sleep duration, bedtime, rising time and cardiovascular disease: Data from NHANES (2017-2020). PLoS One. 2025 Jul 11;20(7):e0326499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0326499. PMID: 40644492; PMCID: PMC12250231.

Zhang Y, Guo J, Hu X, Xie H. Transition of nighttime sleep duration and sleep quality with incident cardiovascular disease among middle-aged and older adults: results from a national cohort study. Arch Public Health. 2025 Apr 4;83(1):91. doi: 10.1186/s13690-025-01577-5. PMID: 40186318; PMCID: PMC11969775.